American girl in Prague: Different views of people from Czechia and USA on the war in Ukraine

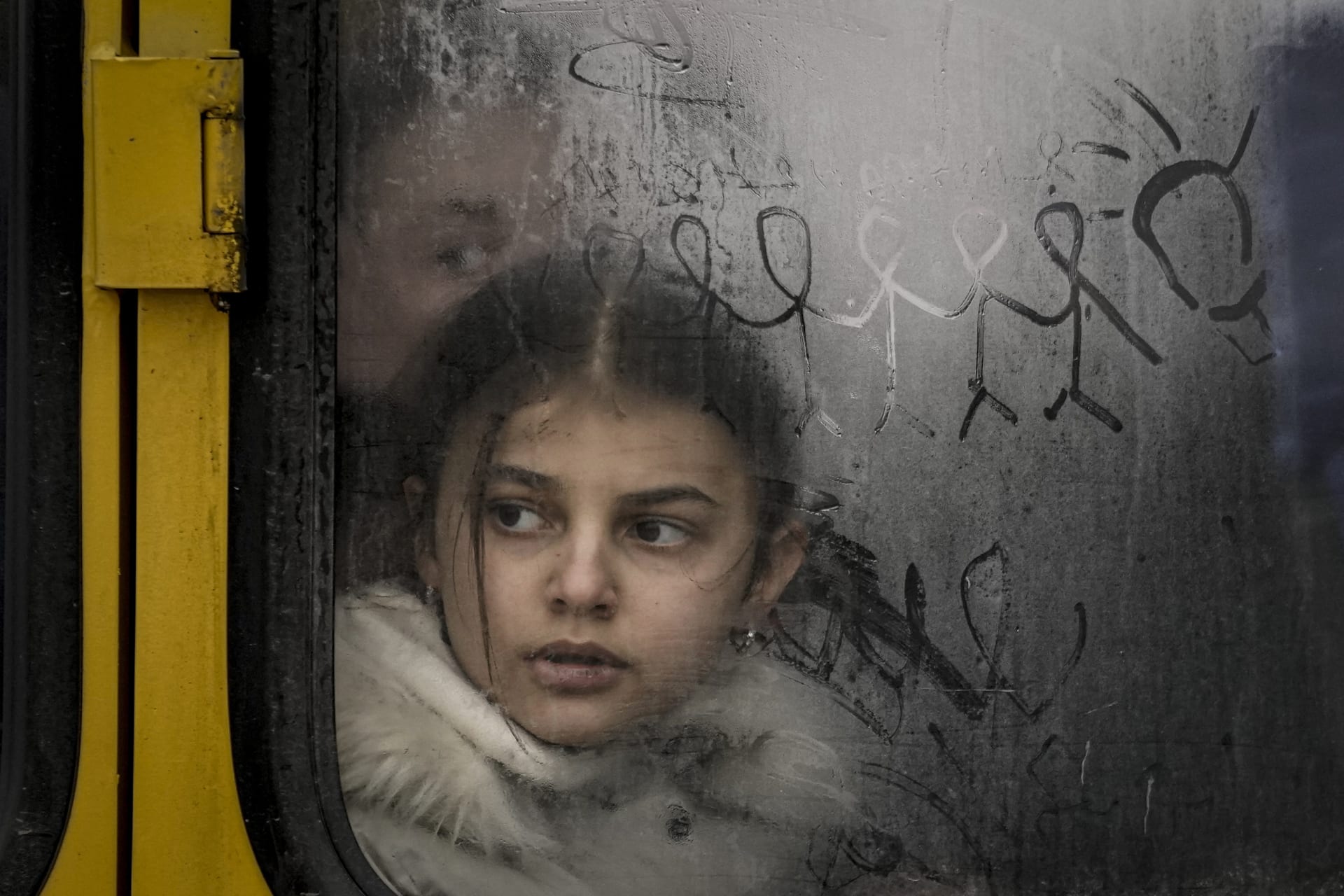

Since the invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, the United States and Czechia have stood as firm allies of Ukraine. One year after the start of the war, Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala estimated that the government had sent 10 billion crowns of military aid and 40 billion crowns worth of weapons. Czechia has also taken in over 500 000 refugees and expects to welcome many more before the end of 2023. Notably, the Czech Republic outpaces the U.S. in aid to Ukraine per capita.

As of May of 2023, America has spent 76.8 billion dollars in military and humanitarian aid. Ukraine receives more American aid today than any other country, including Israel. Additionally, the U.S. is the greatest single contributor of aid to Ukraine.

While the Czech and American governments are strong allies of Ukraine, what do the Czech and American people think about the war? The numbers tell one story. Polling by the Pew Research Center in May determined that 64% of Americans have a favorable view of Ukraine. Additionally, Gallup notes that over half agree with America sending aid to Ukraine.

Čtěte také

Czech opinion polls represent a public that is, overall, sympathetic to Ukraine. According to Ipsos for Deník N, most Czechs support sending aid to Ukraine, and over 75% support economic sanctions penalizing Russia.

As an American and recent college graduate living in Prague, I found myself moved by many Czechs' solidarity with Ukrainians. Back home, at the start of the war, you would see a smattering of Ukrainian flags in yards and as pins in church lapels. As the conflict dragged into 2023, Americans seemed to lose interest. Today in Prague, difficult, material sacrifices are made every day to uplift Ukrainians. In many ways, the war feels more omnipresent here.

Czechs kept asking me: what do Americans think about Ukraine? As one American, it's impossible to represent the 331 million viewpoints of my fellow citizens. For one, my thoughts are partly shaped by an uncommon connection to Czechia. If there is an "average" American (I suspect there’s not), I am a poor representative. I also understand that Czechs are not monolithic in their perspective. For this reason, I thought it would be better to ask real Czechs and Americans what they thought.

To go beyond the polls, I spoke to three Americans and three Czechs. I asked about their perspectives of the conflict, including how they felt about their respective country sending aid, and what they considered an acceptable conclusion. They cannot represent the full wealth of thought on this matter. Still, their views give a small insight into how everyday Czechs and Americans feel. Their comments have been edited for clarity and grammar.

Dr. Vít Dvořák, Ph.D. Czech, Assistant Professor, Department of Parasitology

As I grew up in the 90s’ and I felt very touched by the atrocities of the fights in ex-Yugoslavia, I especially feel grossly disappointed to see that my children, now at the same age as I was then, watch the news similarly horrified.

For Dvořák, the invasion of Ukraine is reminiscent not only of the Prague Spring, but of the disastrous and bloody break up of Yugoslavia.

Reflecting on the February invasion, Dvořák commented, “It shows the little respect that the Russian government has nowadays for peaceful relations among nations in Europe, and its unhealthy and unacceptable imperial aspirations.”

European security concerns also loom over many Czechs. Nearly 75% of Czechs express that the war demonstrates a threat to Czech national security, according to Centrum pro výzkum veřejného mínění.

While I had been worried about the future of my children in the long term due to ongoing climatic and environmental changes, the conflict in Ukraine represents an immediate potential danger. At one point, after the Russians' attempt to suddenly capture Kyiv failed, the military operations turned into a series of Russian losses rather than gains, and the international community very firmly condemned Russia. I was very worried about a potential nuclear attack. I still am.”

“Our children, who were born into a stable European society that saw all warfare as very distant ventures in little known parts of the world, were suddenly confronted with their parents sitting hours in front of a T.V. and nonstop listening to the radio, discussing something that was happening mere several hundreds kilometers away to people who they met.”

Because of this risk, rather than despite it, Dvořák feels Czechs must continue their aid. As for an acceptable ending to the war, Dvořák insists that Ukraine achieves self-determination as a state.

“I feel that only a complete withdrawal of Russian troops from all occupied Ukrainian territories is acceptable in a long term. I can imagine that a temporary armistice may be achieved after Russians withdrawing behind the lines crossed on February 24th, 2022. However, this shall not be cemented by an international peace treaty of any kind and international community shall not push Ukraine into signing such a treaty.”

Ian Schiller, American, Digital Marketer

Ultimately, I think that war generally is a blood-economy which enriches a small number of elites and decision makers while killing and destroying the lives of normal people. I hold that same opinion about this war, as I will for the next war, and the one after that.

Schiller is part of a growing number of young American liberals apprehensive about American involvement in international affairs. While a majority of self-identified liberals are more likely to support U.S. intervention in Ukraine, nearly 10% of Democrats polled by Gallup would like to see less aid sent.

“I understand American involvement and I want the government to do whatever is possible to help innocent civilians in Ukraine. But, I do not want to provide more aid for the same reason that I don't want American gun laws to be loosened; the proliferation of the war machine will only create more violence.”

Schiller also echoes Americans concerned about domestic issues. Less than 1% of Americans consider foreign policy the "number 1" issue facing America today. And, like most Americans, Schiller has no direct connection to the conflict.

“The United States has such big problems domestically that I wish that those billions could be used to fix infrastructure, build communities, and lower income inequality. But I also doubt we would actually use that money for those purposes anyway. Ideally, I would like the U.S. to provide less aid.”

Like nearly a third of U.S. citizens, Schiller would like to see a quicker end to the conflict, alongside a decrease in U.S. military aid provided.

“Any sort of cease fire that could permanently end the violence would be ideal. I think it would be good for the world if the end of the war could be reached diplomatically as opposed to military force.”

Jiří Němeček, Czech, University Student

I'm a little skeptical about government contributions to the Ukrainian military, but when comparing the budgets of the country's rivals, it makes sense to me [for Czechia] to continue contributing.

“I could never have imagined that such a serious conflict could happen in the vicinity of our country in the 21st century. Of course, I do not agree with the aggression with which the Russian government is solving the conflict. I think that nowadays conflicts between states should not be resolved with the help of weapons and the associated loss of lives of their own citizens, but on the contrary, by way of political negotiations.”

Němeček, like Schiller, proposes that his government prioritize humanitarian aid and praises early Czech efforts to support Ukrainian refugees. “I am happy for the way the Czech citizens and the Czech government behaved at the beginning of the conflict. Helping refugees in the form of financial contributions, providing a roof over their heads, and other forms of assistance I greatly respect and take as a right step.”

Němeček is personally connected to the conflict, as his girlfriend is Russian. “My girlfriend was born in Russia and Putin's politics are the reason why she lives here in the Czech Republic.

“Despite the fact that she does not agree with the war, she is burdened by the worsening conditions for Russian citizens and the sudden changes regarding visas. In addition, of course, fear for her family living in Moscow and especially her brothers, who are at risk of mobilization.”

Czechia is amongst several countries in the European Union that have suspended issuing humanitarian visas to Russian nationals.

His girlfriend’s family in Moscow still hopes to leave Russia. But, as Němeček laments, “It is not entirely easy.”

Dr. Jeffrey Jackson, Ph.D. American, Cultural Historian, Professor of History

Although I'm not an expert in Ukrainian historian, I know that although the conflict is recent, the roots of this struggle are old.

History dominates Jackson’s perspective of the conflict. At Rhodes College, Jackson’s classes often focus on the unrest and conflict of 20th-century Europe.

“I can't say the conflict is personally relevant (I don't have any family or friends from Ukraine), but it is relevant to me as a scholar of twentieth century Europe because I can see the echoes of history in the present-day fighting.”

Like other historians and observers of the American military, Jackson hosts concerns regarding American intervention but concedes that, “in this case, supporting Ukraine does seem to be an important action for the U.S. to undertake to limit Russian expansion, which threatens to destabilize the region.” Jackson is amongst the third of Americans that would support sending more aid to Ukraine.

According to the Pew Research Center, support for Ukraine is highest amongst liberal Americans, particularity those who can remember the Cold War. Jackson, who supports the Biden administration's actions in Ukraine thus far, follows this pattern.

As for a conclusion to the war, Jackson, like Dvořák, defers to Ukrainians regarding the end of the conflict.

“The people of Ukraine will ultimately have to determine what is an acceptable conclusion, but at the very least a mutually agreeable settlement that brings stability to the region would be the beginning of a good outcome.”

Almost certainly, this war will join the web of other conflicts that will shape modern Europe, and have a chance of making it into Jackson’s syllabus.

Reed Ostner, American, Product Coordinator

(Americans) should provide less aid as we consistently create destruction that lasts much longer than the fighting. I do not know if less aid will provide a better outcome, but I do know it is the only option we have not tried.

For Ostner, the war in Ukraine is one of many tragedies in the world today. Ostner’s view aligns with many Americans, who see the conflict as a humanitarian crisis—sad, but hardly novel.

“Before this war, I had no opinions on Ukraine, why am I now obligated to make a stand when either outcome doesn't affect me? I do not say this from a position of apathy, but rather, where is the acceptable point to draw a line in the sand between what affects me and what doesn't, halfway across the globe? There will always be conflict in the world.”

“An acceptable conclusion for me is for the fighting and death ending as quickly as possible. The ‘winner’ and ‘loser’ doesn't matter to me.”

To the question of aid, Ostner raises the question—what does the United States government stand to gain from funding the conflict? For many, military assistance from the United States is synonymous with the idea of “nation-building,” an idea that has lost its luster in the wake of the long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“I believe that it is not the U.S.'s job to operate as the world's police although doing so allows us to maintain our own hegemony. The lines between aid that benefits ailing Ukrainians and fighting in their war through supplying everything but foot soldiers is all for optics in my opinion.”

While the majority of Americans support sending aid to Ukraine, nearly a third of Americans would like to see the U.S. send less aid, according to Gallup.

Andrej Kaplin, Czech, University Student

Within the E.U., [Czechia] is one of the leading supporters in terms of the number of inhabitants and the size of the economy, and citizens can be proud that the state is not afraid to indirectly confront a much larger aggressor.

A student in his final year of study, and a strong supporter of Ukraine, Kaplin is, like many Czechs, invested in seeing Ukraine prevail.

Recalling the first week of the invasion, Kaplin said, “I have been following the conflict since the very beginning. I stayed awake the first night because of it and stupidly updated social networks and news sites all the time so as not to miss a single update on the current situation.

“I follow the stories of Ukrainians. I try to help them as much as possible, and I don't intend to stop.”

Kaplin feels that Czechia has taken an admirable stance for Ukraine.

“This is an almost unprecedented situation that Europe has not had to face for a long time and for which it was not prepared. In theory, it might not have happened at all if leading Western politicians had paid attention to Ukraine since 2014, in one of the seeds of the current war. Reactions in the form of a policy of appeasement and hole-in-the-wall sanctions, through which relations and trade were further deepened, did nothing to deter Russia from preparing a plan to invade Ukraine.”

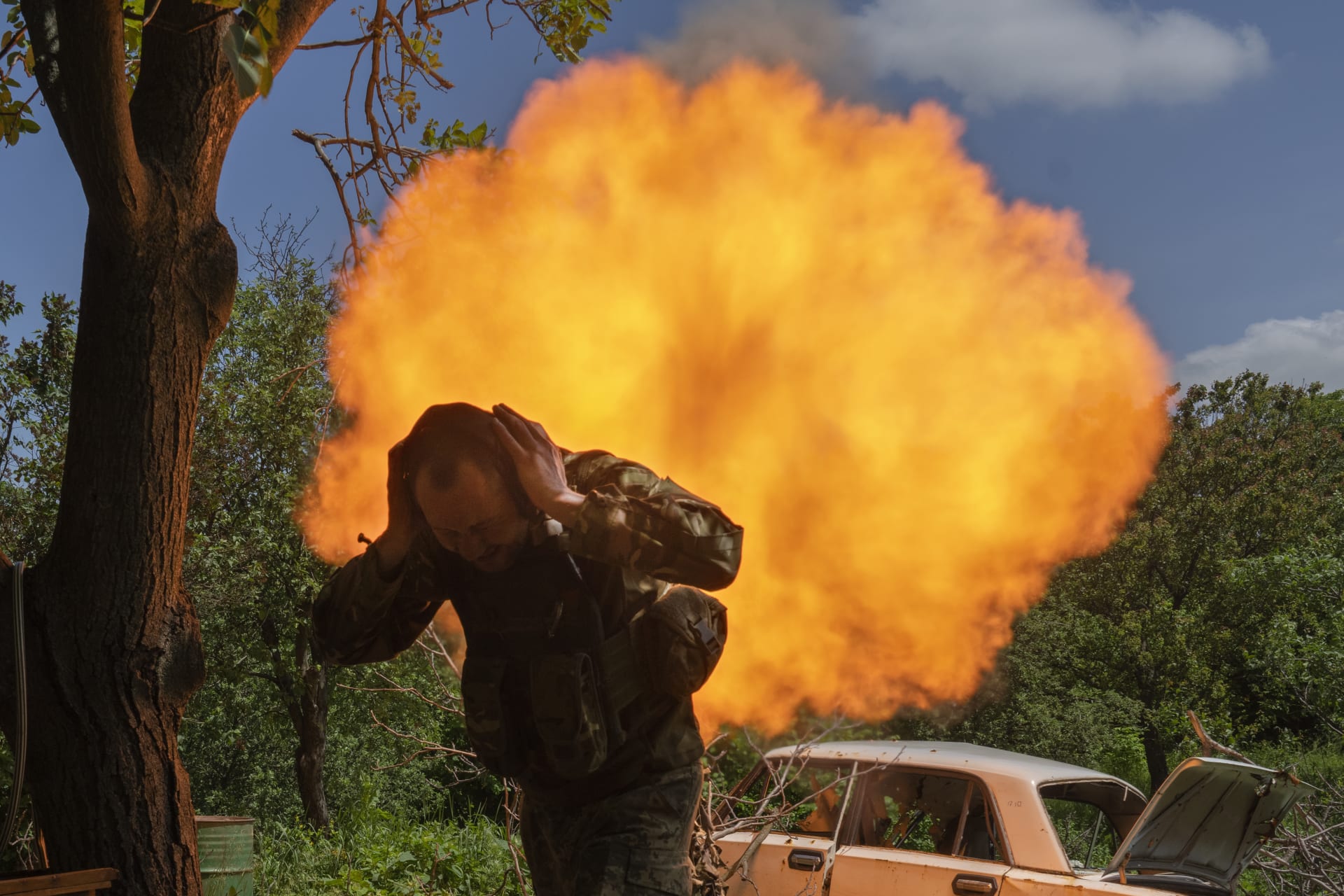

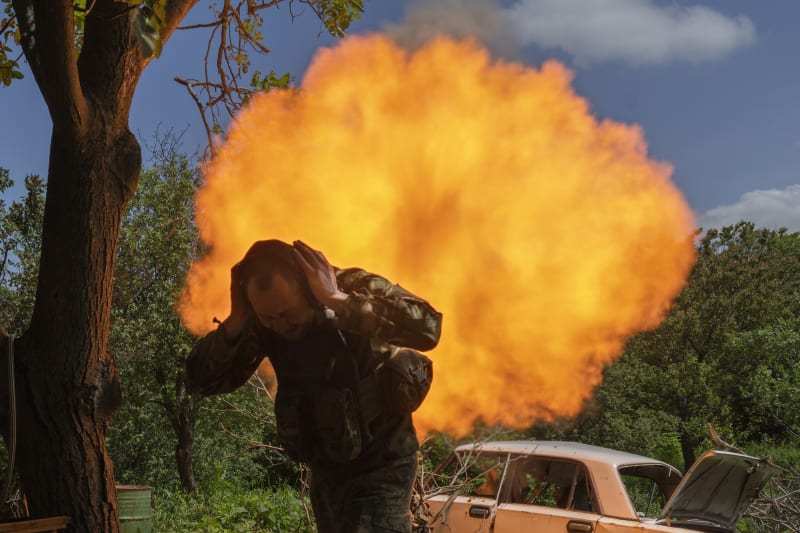

“Even at the moment of the invasion of the Russian troops into Ukraine, some European powers were not able to react adequately, and it was not until the worldwide publication of photos of the massacre in Buča that these countries were sufficiently motivated that the time to act finally came.”

“I value all the more, from the very beginning of the war, the strong involvement of the Czech Republic, the Baltic countries, Scandinavia and Poland.”

While the war's end is not in sight, Kaplin hopes for a total victory for Ukraine. For him to be satisfied, he would need to see a “complete withdrawal of Russian troops, return of borders to pre-2014 status, [and a] demilitarized zone along Ukraine's borders with Russia and Belarus.”

But for now, Kaplin maintains that Czechs “can be proud that the state is not afraid to indirectly confront a much larger aggressor.”